Robert Hugh Benson’s prophetic vision of Utopian Humanism

Quinn Abbey, Co. Clare, Ireland. Photo: Niall Buckley.

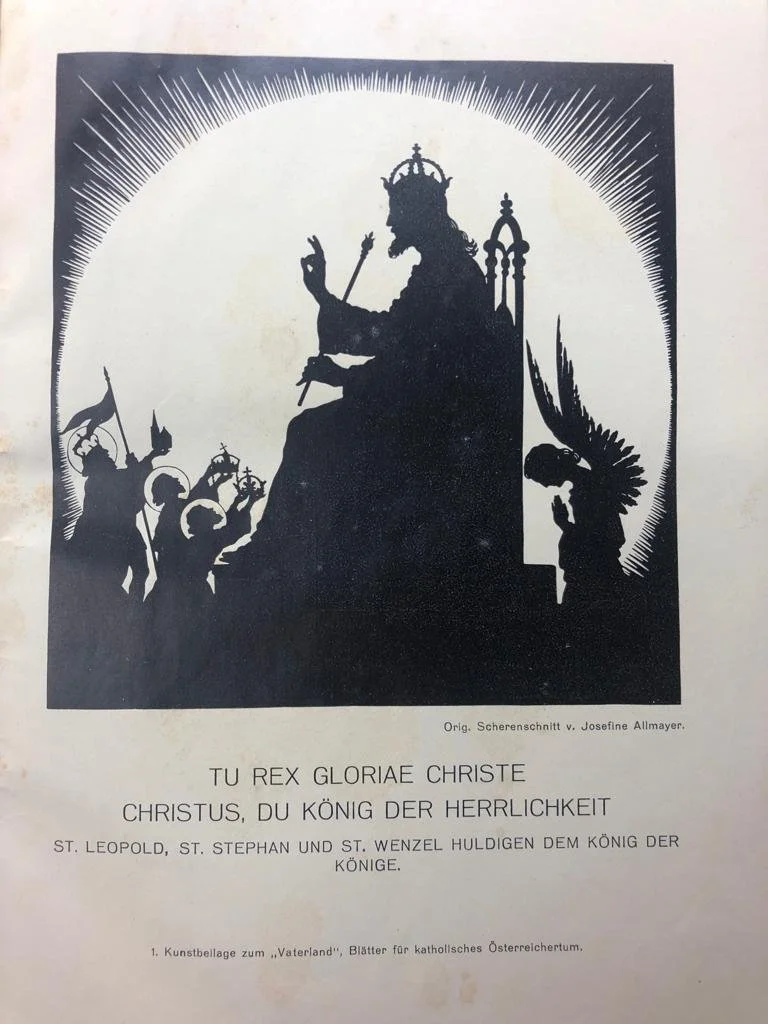

With the approaching feast-day of Christ the King, it is well worth considering who or what reigns in the heart of modern Man. Pope Pius XI when establishing this feast in the liturgical calendar with his 1925 encyclical Quas primas declared: “that as long as individuals and states refused to submit to the rule of our Saviour, there would be no really hopeful prospect of a lasting peace among nations […] the result is that human society is tottering to its fall, because it has no longer a secure and solid foundation.”

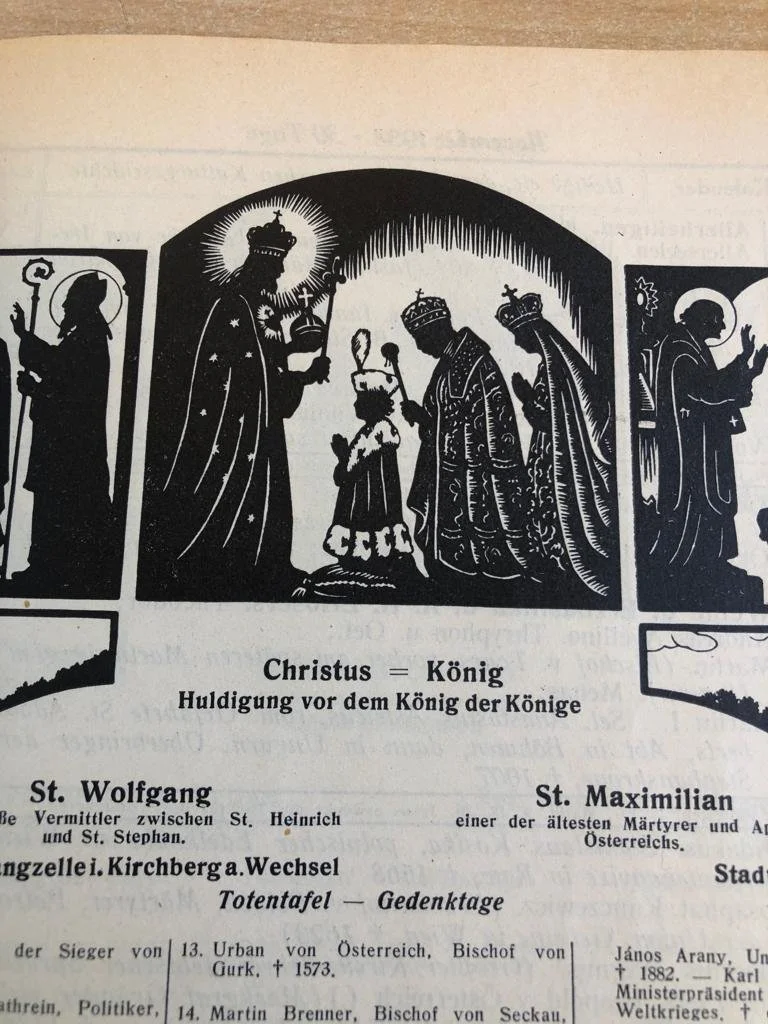

Blessed Charles of Austria, Empress Zita and Crown-prince Otto von Habsburg pay homage to Jesus Christ, the King of kings.

Early 20th Century Europe was suffering from an utopian idealism which sought to uproot this traditional solid foundation and supplant it with a new order based on superficially new but deceptively old ideas. That of man as his own sovereign.

“The punishment of the idealist consists in the triumph of his own cause.” It is with these words that anti-Utopian South American thinker Nicolás Gómez Dávila opens the second volume of his 1977 Escolios a un Texto Implicito. Dávila, profoundly influenced by his exposure to counter/dark-enlightenment German Romantic philosophy, which he sought to integrate and synthesise with his Catholic traditionalist worldview, came to see human history as consisting of a constant struggle between two forces. That of men subordinating themselves to God and that of men who seek to supplant God as the ultimate arbitrator of truth and morality.

In this battle of ideas Dávila stands on the shoulders of such well-known intellectual giants as Thomas More, Edmund Burke and Dietrich von Hildebrand. Men who foresaw and experienced tyranny in their own lifetimes. Their voices echo through the ages and carry no less wisdom for our own era than for our ancestors.

One such influence not so well-known today however, is deserving of particular examination, that of Robert Hugh Benson. For all five men, the root of man’s woe lies in his refusal to work within the parameters of natural law as set forth by divine authority. In this way there exists a perfect continuity between the Garden of Eden, Tower of Babel, Protestant Reformation, French Revolution, National Socialism and Soviet Socialism.

In contrast to the angels who made their decision to serve or not serve in a singular moment of time and which carried with it irrevocable consequences reverberating in perpetuity, man, in every generation, and indeed every day, must choose for himself which banner to stand behind.

Utopian manifestos and dystopian predictions from 4th-Century BC Plato's Republic, Thomas More’s 1516 satirical work Utopia, to modern day bestsellers such as Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World or George Orwell’s 1984, have captured the minds and imaginations of many a reader.

Fr. Robert Hugh Benson in Catholic clerical attire.

While no age is free from evil, some generations experience a greater flourishing of virtue than others. It is in this light, upon reflecting on the recent past and present situation, that one ponders what the future might bring. One such ponderer is Robert Hugh Benson, notable turn of the 20th Century convert to Catholicism, ordained priest and writer, both polemic, prolific and prophetic.

While well-read souls might well be familiar with Benson for his works of historical fiction such as By What Authority and Come Rope, Come Rack, it is Benson’s 1907 Lord of the World which most adequately grants insights to his primary critique of his own age (and no doubt applicable our own too). It is within these pages that Benson commits himself to providing a literary rebuttal to the neo-pelagianist mindset of materialistic (anti-supernatural) humanism and it’s ensuing Gleichmacherei, a levelling or flattening uniformism which sees distinctions as inherently indicative of injustice.

Edmund Burke in observing the French Revolution from across the English Channel commented that “People will not look forward to posterity who never look backward to their ancestors.” For Burke society was a a social contract between generation dead, born and yet to be born. A perfect complementary continuity of past, present and future. It is this violent rupture in continuity that dominates The Lord of the World. The spirit of liberty, equality and fraternity, propagated by the malicious plotting of freemasonry is the main motif of Benson’s envisioned near-future dystopia.

Edward VII, King of Great Britain and Ireland (1901-1910) in freemason attire.

Benson’s imagined early 21st-Century Britain is one of aviation, dishwashers, Esperanto, social credit scores, abortion, nuclear weapons (what Benson terms Benninschein explosives), superficial pseudo-intellectualism, free trade, cult of utility, euthanasia, secularist homogeneity, Pan-European government and German apostate bishops. One in which tradition and faith are seen to be mere remnants of declining dark medievalism. One in which the ever onward march of progress goes hand-in-hand with the withdrawal of religion from the public and private sphere.

Dietrich von Hildebrand recounts from his 1943 exile the absurdity of using “Middle Ages” or “Mediaeval” as a pejorative; “Indeed, the Middle Ages were irradiated by a spiritual light which is lacking in our modern times, and those who speak of the mediaeval epoch as the "dark" Middle Ages must be highly suspected to be themselves still in the darkness of the spiritual decomposition which paved the way to the totalitarian antipersonalism and the reign of Antichrist.”

What von Hildebrand refers to here as “the totalitarian antipersonalism and the reign of Antichrist” is also central to the thinking of Fr. Benson. In his Dystopia, the 20th Century consisted of a political struggle between collectivist Labour and individualist Tories, the charismatic character Felsenburgh being indicative of the culminating assent to power of the former.

Naturally, while the Catholic Church is not foreseen to be immune to such destructive forces of upheaval, she is viewed by contemporary characters for what she is, the unshakable rock antithetical to the agenda of the proponents of Gleichmacherei. The Catholic Church, unlike Anglicanism with its willingness to compromise with the spirit of the age, is foreseen to be the last western holdout to the liberation of man from the superstition of a personal God.

For Benson these seeds were germinating within his own lifetime. The son of head of the Church of England, the Archbishop of Canterbury, he himself was ordained in CoE in 1895 (a year before Pope Leo XIII’s 1896 papal bull Apostolicae cura regarding the “Nullity of Anglican Orders”), converted in 1903 and was ordained in the Catholic Church the following year.

Concerned with societal trends of Modernism within the Church as the infiltration of the errors of worldly relativism, Benson’s The Lord of the World unleashes a scathing critique of the technocratic bureaucratisation of all aspects of human life ordered towards totalitarian collectivism.

In this establishing of a new world order, the Church was not the sole obstacle. Univeristaries too were seen to be obsolete edifices upholding the old “reactionary” order. Their fate is described by Benson as the same suffered by monasteries under Henry VIII, subverted and suppressed, relegated to mere regime mouthpieces and later liquidated. The humanities erased and “Psychology coming to the rescue of crude materialism”.

The book follows Fr. Percy Franklin's attempt to navigate the assault of Secularism from within the west and Islam from without, the two forces coalescing under the would-be messiah Felsenburgh. As one newspaper, The New People declared: ”No more a crying after a God that hides himself but to Man who has learned his own divinity, the supernatural is dead, rather we know now that it has never been alive.”

Utopian idealism does not emanate from a vacuum, it often stems from civilisational decline and furthermore the denial of such a collapse. The resulting cognitive dissonance manifesting itself in an ever more persistent doubling-down on the very root of such a collapse. As Dávila asserted in 1977: “Dying societies accumulate laws like dying men accumulate remedies” and that “[t]he individual shrinks in proportion as the state grows”

Be it Giovanni Pico’s 1486 Oration on the Dignity of Man or Rousseau’s 1762 Du contrat social, such ideas are in fact no more than a re-formulated syntheses of neo-pelagianist luciferianism. The belief that man, independent of God, can ascend to earthly or celestial greatness.

This is manifest in the leader of the UK Communists, Oliver Brand’s, attempt to reconcile his own political ideology with the residual Catholic faith of his dying mother. For him and his wife Mabel, the rosary is something that provides feeble-minded old ladies with psychological comfort before death, having no objective spiritual power of its own beyond the subjective perception that individuals place upon it. For the Brand couple, Christian charity and Latin are relics of Medieval superstition, while masonic universal fraternity and Esparento are vehicles for enlightened progress.

While the Catholic Church persists as a sub-culture of UK society, with many fleeing to Ireland which Benson optimistically predicted would be a bastion of the traditional order, the continent across the channel has reordered itself into a Pan-European Marxist Confederation. The Church retreating from Marxist Italy and consolidating what temporal influence it had remaining in the eternal city of Rome. As Benson writes; “Rome had been given up whole to that old man in White, in exchange for all the parish churches and cathedrals of Italy and it was understood that mediaeval darkness reigned there supreme”

Like Cardinal John Henery Newman before him, Benson imagined what a (pre-1929 Laternal Treaty) resolution to the ongoing early 20th-Century Cold War between Freemasonic Italian nationalism and traditional Papal territorial claims would look like.

Benson, while in many respects prophetic, was obviously not inerrant in his predictions. His view that Ireland would offer strong resistance to the secularist progressivism, misguided, and his view of the Church hierarchy as active opponents of the worldly spirt of the day, sadly naive.

Rome in The Lord of the World was to be a hotbed of a neo-luddite resistance to material and spiritual modernity, a supernatural place of multicultural supranationalism diversity where exiled dethroned monarchs resided and seminarians studied. One in which according to Fr. Percy, the Mass, contemplative prayer and the rosary were the antidote to the attempt of secularism to usurp the role of the Church as the vehicle of man’s salvation

Rome in Benson’s mind, while suffering immensely, did not wish to sell out the underground Catholic faithful. Fr. Percy is tasked with accumulating daily reports on the state of the Church in England and at no point is compromise with advancing secularism even considered on an institutional level. Apostasy is followed swiftly by charitable excommunication. In his mind it is a period of persecution and purification. In Fr. Percy’s own words; “separating the Sheep and the goats”.

As state atheism advances Benson predicts the reverse engineering of a secular religion in the form of worshipping the state. One is obviously reminded of Hitlerism, Stalinism and Maoism of history, but also present day phenomena where “hate-speech” laws replace the blasphemy laws of old. A society where one is instructed to unquestionably “trust the experts” and in which uncontrolled sexuality and racial animosity are sanctified.

Once again one can turn to the words of Dávila: “Violence is not necessary to destroy a civilisation. Each civilisation dies from indifference toward the unique values which created it.” This predicted persecution of the Church was therefore in Benson’s mind in continuity, or rather the fulfilment of the 16th-Century Protestant Revolt. One in which man is compelled by state authority to confess Christ King of kings and suffer death of the body or succumb to apostasy and suffer a death not temporal, but far more grave.

Niall Buckley,

October 2022.